This fact sheet provides an overview of the different forms and laws of surrogacy around the world. We’ll look briefly at how surrogacy is treated in different countries, as well as its definitions, concepts, regulations, scope and origins.

l/The different types of surrogacies

Definition: Surrogacy is defined as the social practice of recruiting, with or without payment, a woman to carry one or more children, whether or not conceived with her own eggs, with the aim of giving them to one or more persons (the commissioning parents) who wish to be designated as the parents of these children. Private intermediaries play a fundamental role in this process. These can be private infertility agencies or clinics, doctors or lawyers and, more recently, banks offering bank loans to commissioning parents to finance the cost of surrogacy.

Commercial surrogacy: The most common form of surrogacy, the child is obtained through a contract between the commissioning parents and the surrogate. The contract stipulates the amount she is to receive, called “compensation”, the terms and conditions of payment, and the numerous obligations imposed on her: behavior, lifestyle….. The contract is the sole authority governing the relationship between the parties. The surrogate mother renounces her most basic rights for the duration of her pregnancy, while the commissioning parents are only obliged to pay the agreed sum.

Regulated or supervised surrogacy: a restrictive approach to surrogacy in which the state authorizes the practice by law, defining the conditions of access, remuneration, transfer of parentage, etc. The aim of regulation is to protect all parties involved. The aim of regulation is to protect all parties to the contract by organizing the process to limit excesses. However, we know that the few legislative changes that guarantee the rights of surrogates are often watered down and swept aside under the pressure of the market.

Altruistic, Solidarity or Ethical Surrogacy: Variations of Commercial Surrogacy The positive qualifiers attached to the practice are intended to distinguish it from the commercial version, which is likened to the sale of children. It is presented as virtuous and, to exonerate itself from the accusation of selling children, it limits the sums paid to the surrogate mother, described not as remuneration but as compensation, while protecting the emoluments of all those involved, whose intrinsically commercial approach is not questioned.

Intra-family surrogacy: limited to cases where there is an emotional and family bond between the surrogate and the commissioning parents (recently introduced in Portugal and India). It is used to limit access to surrogacy as much as possible, but still places women at the service of reproducing “the line”, either voluntarily or through pressure or coercion.

International, transnational or cross-border surrogacy: the commissioning parents reside in a country other than that of the surrogate mother. Once the child is born, the child is taken from the mother and transferred to the commissioning parents country.

Domestic surrogacy: The commissioning parents reside in the same country as the surrogate.

Traditional surrogacy: The surrogate is inseminated with sperm provided by the commissioning parents. The embryo is created from the inseminated sperm and therefore from the surrogate’s own eggs, which are genetically linked to the newborn.

So-called “gestational” surrogacy: with IVF, the surrogate mother no longer has any genetic link to the child, since the two gametes at the origin of the embryo come from the commissioning parents and/or donors. Although more dangerous for the surrogate mother and the future child (see medical risk sheet), this technique has gradually replaced artificial insemination, which was said to make the surrogate mother “abandon her own child” since it was genetically linked to her. Whether IVF or artificial insemination, it is the surrogate mother’s child that is given to the commissioning parents.

In all these cases, pregnancy is a biological function, so the surrogate is the biological mother of the child she gives birth to.

II/ International regulations

Table taken from a study by ICAMS and ENoMW 2021-2022 “Migrant women and reproductive exploitation in the surrogacy industry”[1].

| REGULATED | ILLEGAL | NOT REGULATED (no specific law regulating surrogacy) |

| South Africa | Germany | Algeria

|

| Albania | Austria | Angola

|

| Belarus | Bulgaria | Benin

|

| Cyprus | Spain | Cameroon

|

| Denmark | Finland | Ghana

|

| Greece | France | Niger

|

| Hungary | Italy | Nigeria

|

| Netherlands | Latvia | Uganda

|

| Portugal | Lithuania | Senegal

|

| Czech Republic | Malta | Andorra

|

| United Kingdom | Norway | Belgium

|

| Russia | Sweden | Bosnia Herzegovina

|

| Ukraine | Switzerland | Ireland

|

| India | Saudi Arabia | Luxembourg

|

| Israel | Azerbaijan | Poland

|

| Thailand | Cambodia | Romania

|

| Vietnam | Singapore | Afghanistan

|

| Brazil | Costa Rica | Armenia

|

| Colombia | Montenegro | Bangladesh

|

| Ecuador | Dominican Republic | North Korea

|

| United States | Turkey | South Korea

|

| Mexico | Japan

|

|

| Uruguay | Nepal

|

|

| Australia | Philippines | |

| New Zealand | Argentina

|

|

| Georgia | Puerto Rico

|

|

| Hungary | Croatia

|

|

| San Marino

|

||

| Taiwan

|

III/ Geographical analysis of surrogacy

In Europe, the shared value of human dignity has resulted in the prohibition of surrogacy

In response to the horrors of Nazism during the Second World War, the question of the right to human dignity became paramount, to the point of being the first article of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union[2]. Surrogate motherhood is widely considered to be an affront to human dignity, which is why it is prohibited in about twenty European countries. Switzerland is a special case, where the ban is enshrined in the Federal Constitution.

In Anglo-Saxon countries, a culture of pragmatism promotes regulation

Many countries within the former British Empire, such as the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa, have opted for a regulatory approach. They believe that since surrogacy is already in practice, regulating it is more practical than outright abolition. This pragmatic stance aims to establish rules to prevent abuses and safeguard the interests of all parties involved. Unfortunately, due to market pressures, the regulations governing commissioning parents are gradually being relaxed or eliminated. For instance, in the United Kingdom, a revision of the 1985 law has reduced the so-called withdrawal period from 6 months to just 6 weeks. This period allows the surrogate mother to reconsider the transfer of parentage to the commissioning parents and, theoretically, decide to retain the child. Furthermore, advertising is now permitted to attract more potential surrogate mothers, further illustrating the trend towards deregulation.

The United States, with its emphasis on individual freedom, and the former USSR republics, often criticized for their inadequate focus on human rights, lean toward endorsing commercial surrogacy

In neoliberal countries like the U.S. and various Latin American nations, commercial surrogacy is on the rise in the name of individual freedom, anchored in the principle of absolute self-determination (the right to make decisions about one’s body in commercial contexts) and entrepreneurial liberty. For instance, Washington State legalized commercial surrogacy in 2018, and New York State followed suit in 2020.

Since the early 1990s, countries in the former USSR, including Georgia, Russia, and Ukraine, have opened their doors to cross-border commercial surrogacy. This activity, seen as a source of foreign exchange, is considered just another facet of a rapidly expanding industry that often exploits economically and socially vulnerable women, including refugees from the Donbass region of Ukraine. However, as of 2022, these countries are gradually closing their borders to this practice due to its association with human trafficking.

New areas open to surrogacy

The case of Kenya

Indian providers have turned to Kenya to compensate for the decline in their business since national regulations in their country became more restrictive. By promoting a new destination, their sales pitch is clear: Kenya is presented as a credible alternative to India, Nepal or Cambodia, which have closed their doors to cross-border surrogacy or to the United States due to high costs.

However, another operator has reversed its position after promoting Kenya as a new “low-cost” procreation destination, citing the country’s poor medical facilities and high neonatal mortality rate (37 per 1000).

Mexico as new low-cost destination

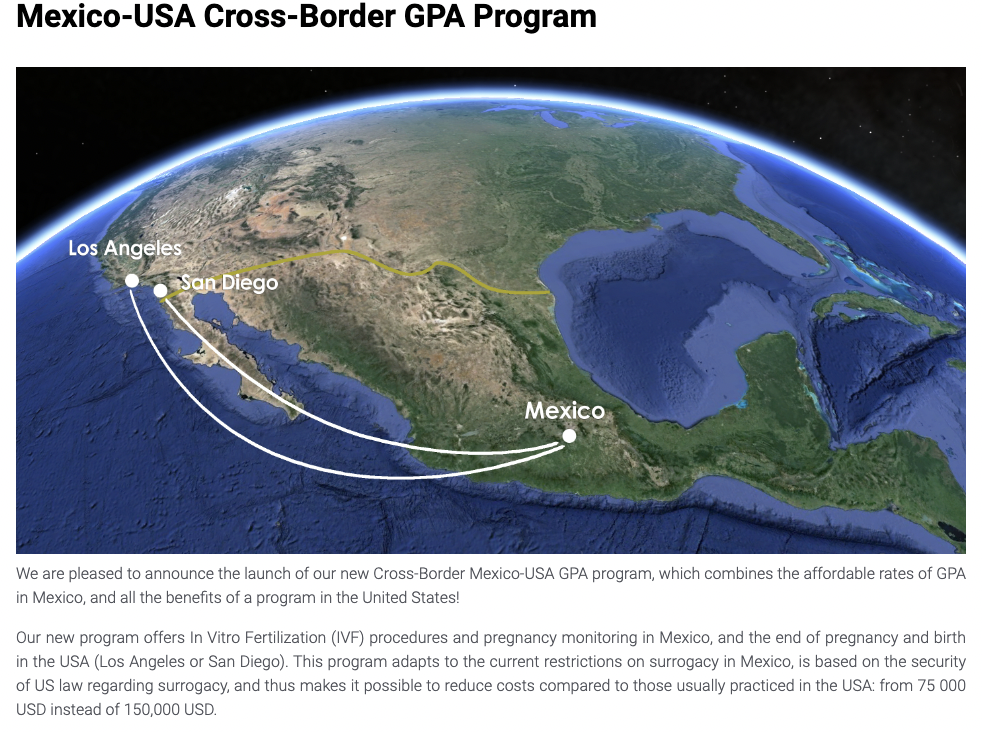

As a country bordering the United States, more and more agencies are offering “cross border” surrogacy services, i.e. the birth takes place in the United States in order to obtain American citizenship. Clients benefit from low Mexican prices, which are half of the US prices.

Below is an advertisement for USA-Mexico Cross Border Surrogacy from Cefam Surrogacy Mexico[3]:

[1] http://abolition-ms.org/en/non-classe/migrant-women-and-reproductive-exploitation1-in-the-surrogacy-industry-joint-investigation-by-enomw-icasm/

[2] http://fra.europa.eu/fr/eu-charter/article/1-dignite-humaine

[3] https://www.cefamgpamexique.com/nos-programmes/programme-gpa-cross-border-mexique-usa/